The Complete Guide to Cross-cultural Design

Cross-cultural design is not a walk in the park. To be effective, designers need to consider not only language differences, but cultural tendencies, values, customs, and taboos.

Hello, Bonjour, Hola, 你好, Guten Tag, こんにちは, Привет, Merhaba, Jó Napot, Здраво!

Designers at global companies frequently work with geographically distributed teams. We also regularly work on digital products designed for global consumption for clients located all over the world. Yet designers, forgetting there’s a wider world out there, continue to live in a bubble and tend to focus only on their local culture, traditions, and language.

Cross-cultural design indisputably presents complex challenges—both linguistic and cultural. Nevertheless, most designers wrongly assume that designing products for different cultures simply requires language translation (localization), switching currencies, and updating a few images to represent the local culture. The road to successful cross-cultural design with great UX is far more complicated and rife with pitfalls.

Who can forget the seminal cautionary tale of why Chevrolet’s “Nova” failed in Latin America? The story claims the branding failed because the name “Nova” means “no go” in Spanish. This tale of substandard branding has been recounted to generations of business students as an object lesson in the failure to do reliable, in-depth cross-cultural research. There’s only one problem with the story: It’s not true.

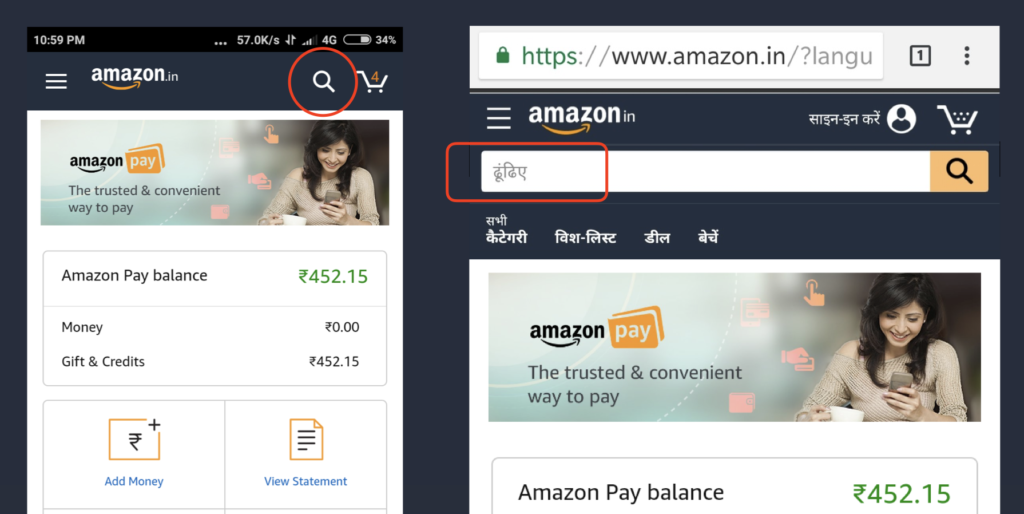

When launched in India in late 2018, Amazon was faced with a serious problem caused by a lack of cultural insight and comprehensive UX research. They couldn’t figure out why customers in India weren’t using one of their primary drivers for revenue: searching for products to buy on the homepage of the mobile site. It turned out that the magnifying glass icon was not something people associated with search in India. It made no sense at all to them.

When the UI was tested, most people thought the icon represented a ping-pong paddle! As a solution, Amazon kept the magnifying glass but added a search field with a Hindi text label to let people know this was where they could initiate a search.

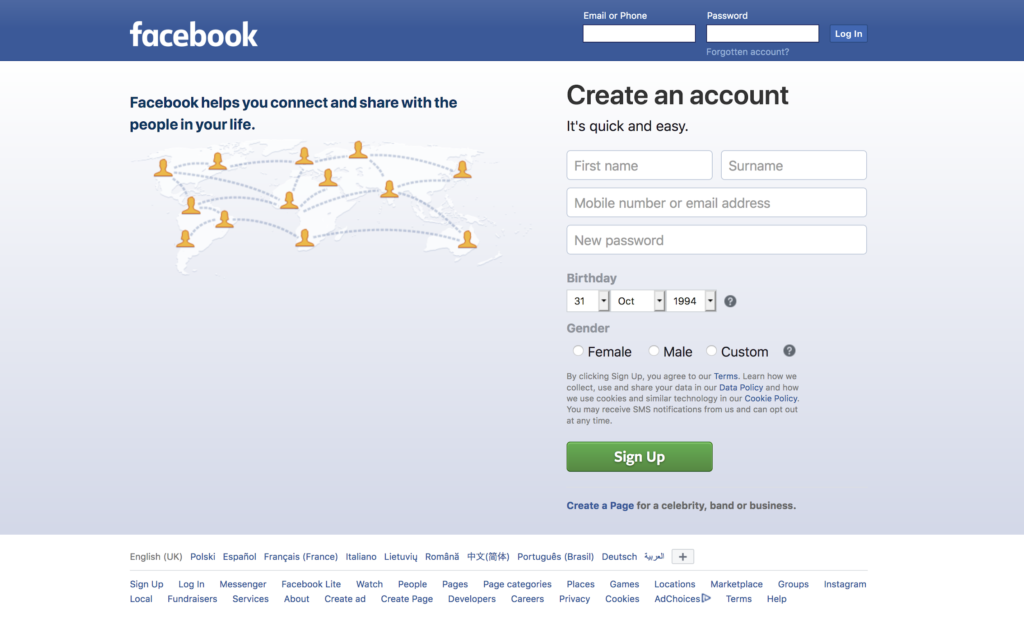

When designing cross-cultural products, designers not only have to contend with different languages, dialects, and dimensions of national culture, but also cultural differences in color psychology and mental models. Furthermore, reading direction from culture to culture adds another layer of complexity as text can be written left-to-right (LTR), right-to-left (RTL), and top-to-bottom.

With some languages, “mirroring designs” is something designers need to consider when designing for both LTR and RTL languages. Consideration should be given to everything from text to images, to navigation patterns and CTAs (calls-to-action).

Here’s Facebook’s homepage in English:

And here’s Facebook’s homepage in Arabic where the layout is reversed (mirrored):

Using culturally appropriate imagery in products reaching across cultures is also something designers need to be aware of. An image that may be perfectly acceptable in Western cultures may be considered inappropriate in some Middle Eastern countries. Varying attitudes towards gender, clothing, and religion in different parts of the world calls for designers to be extra careful when working with images.

If a designer is not familiar with a particular culture, it’s crucial that they dedicate some time to researching what is appropriate in tone from culture to culture, being sure to include every element in the UI: text, imagery, iconography, microcopy, and more.

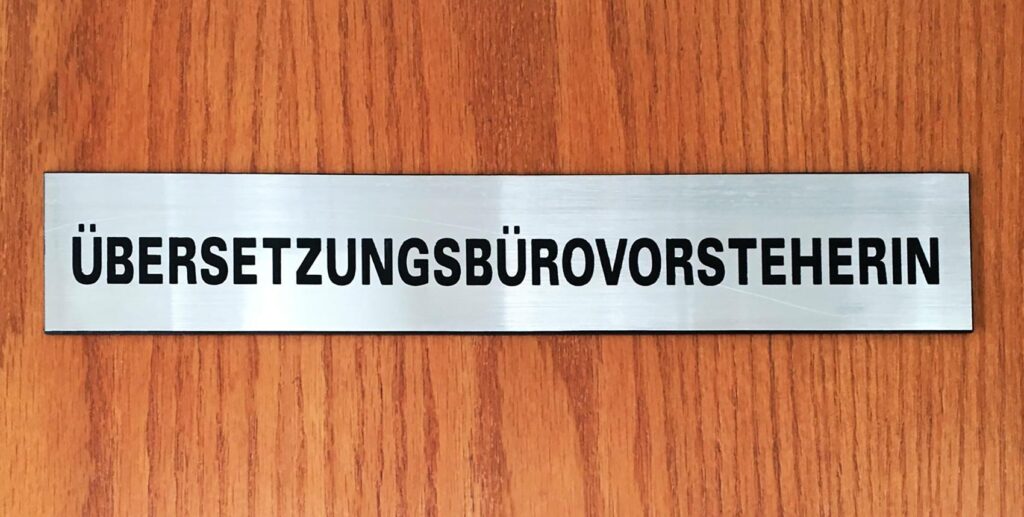

Designers also have to account for text in different languages, known as “text expansion.” Working with English, German, and Japanese for the same piece of text will yield very different results. Going from English to Italian phrases will at times cause text expansion of around 300%! Not accounting for differences in word lengths in a variety of languages or giving UI elements ample padding will create a boatload of work down the line because a tsunami of screens will need to be adjusted to accommodate the switch to another language.

The Seven Dimensions of Cross-cultural Design

Designing for global markets has been around for a long time and predates designing for digital products. Cross-cultural design research is rooted in the work of two individuals: Fons Trompenaars and Geert Hofstede.

Trompenaars is widely known for “The Seven Dimensions of Culture,” a model he published in “Riding the Waves of Culture.” The model is the result of interviews with more than 46,000 managers in 40 countries.

Rather than distinguishing cultures simply by language, Trompenaars established seven differentiating qualities:

- Universalism versus particularism. Do people place value on rules, laws, and dogma? Or do they believe the world to be circumstantial?

- Individualism versus communitarianism. Do people believe in personal freedom and achievement? Or is the group greater than the individual?

- Specific versus diffuse. Are work and personal lives kept separate or do they overlap?

- Neutral versus emotional. Do people make great efforts to express their emotions or are they kept in control?

- Achievement versus ascription. Are people valued for what they do or who they are?

- Sequential time versus synchronous time. Some people like events to happen in a striated sequence. Others believe that the past, present, and future are an interwoven continuum.

- Internal direction versus outer direction. Some cultures profess to control nature and the environment, while others believe the opposite.

Hofstede also contests conventionally narrow views of language and culture. Everyone knows that our spoken accents develop based on where we grew up. Less talked about, though, is that how we feel and act is also a type of accent influenced by our locale.

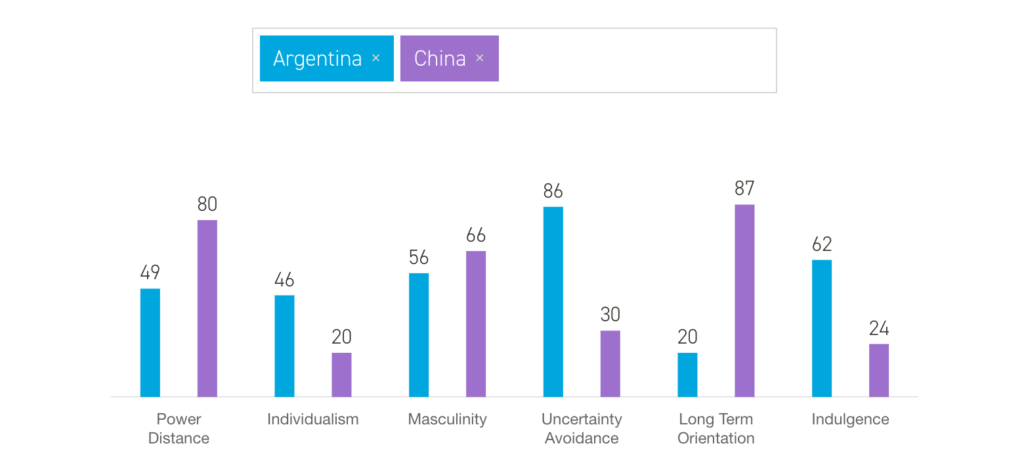

The cultural dimensions represent cultural tendencies that distinguish countries (rather than individuals) from each other. The country scores on the dimensions are relative, as we are all human, and simultaneously we are all unique. In other words, culture can be only used meaningfully by comparison.